BLOG > mRNA & LNP > White paper: Ionizable lipids for mRNA-LNP and siRNA-LNP

This white paper examines the development of Lipid Nano Particles (LNP) formulations for mRNA delivery, focusing on innovations at OZ Biosciences. We present data demonstrating how ionizable lipid composition influences transfection efficiency across various cell lines and affects in vivo biodistribution, with particular emphasis on intra venous administration in murine models.

Introduction

The emergence of mRNA-based therapeutics has created an urgent need for efficient delivery systems capable of protecting nucleic acids from degradation while ensuring cellular uptake and endosomal escape¹. Lipid Nano Particles have proven to be the most successful delivery platform, as evidenced by their use in COVID-19 vaccines². However, achieving cell-type specific delivery and optimal biodistribution remains challenging.

OZ Biosciences has developed a series of LNP formulations that demonstrate differential transfection efficiency across cell types in culture and tissues in living organisms. This white paper presents comparative data on how various ionizable lipid compositions affect mRNA delivery both in vitro and in vivo settings, with special focus on intravenous injection as a route of injection for targeting various organs.

LNP Composition and Design Principles

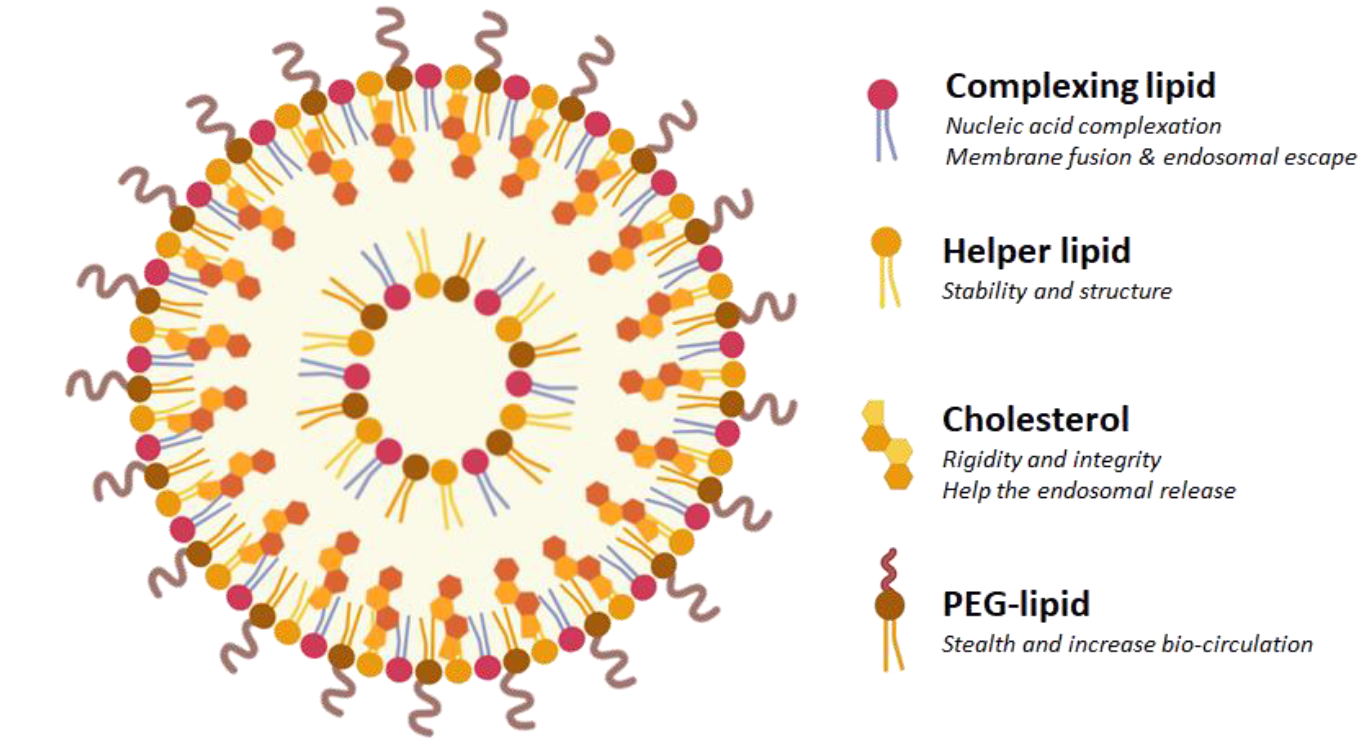

Standard LNP formulations consist of four key components in varying doses. The complexing lipid, in our case a proprietary ionizable lipid, counts for 40-50 mol%; the helper phospholipid that stabilizes and structures the LNP, for 10-20 mol%; the cholesterol that ensures the rigidity and integrity of the LNP, represents 35-45 mol% and finally, the PEG-lipid that increases the bio-circulation represents 1-3 mol%.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of a lipid nanoparticle composed by a mixture of four chemical components: complexing (ionizable) lipid, helper phospholipid, cholesterol and stealth-lipid. Each compound holds its own specific function and is present at a defined concentration.

The ionizable lipid component is critical for endosomal escape and help to determine much of the LNP's cell-type specificity and biodistribution profile³.

The formulation is done by microfluidic or jet mixer where the active ingredient is mixed with lipids before adjustment by dilution. The system of mixing depends on the application and the volume required.

All our lipids are designed based on our patented structure that allows to change the type and length of the carbon tail, the polar head and the bio-inspired molecular template. Each created LNP has thus a specific size and electrical charge, as well as a defined mRNA encapsulation rate that are validated through extensive quality controls (Table 2).

| Items | Specification | Standard QC | Superior Grade QC |

| Identity | Size | ✔ | ✔ |

| Charge | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Content | Encapsulation efficiency | ✔ | ✔ |

| RNA concentration | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Safety | Sterility | ✔ | ✔ |

| Endotoxin | ✔ | ||

| Mycoplasma detection | ✔ | ||

| Characterization | Lipid content | ✔ |

Table 2: Quality controls depend on the grade of the required LNP. While Standard QC includes the validation of size, charge, encapsulation efficiency, RNA concentration and sterility, Superior Grade QC extends its checks to additional aspects related to endotoxin and Mycoplasma detection as well as the dosage of lipids. Superior Grade QC thus offers a more comprehensive evaluation to ensure superior quality and safety.

Rationale

The role of ionizable lipids in cell-type specificity

The influence of ionizable lipids on transfection efficiency depends on multiple factors related to cell origin and characteristics⁴. Primary cells and cell lines from different tissues exhibit varying membrane compositions, endocytic pathways, and metabolic activities. For instance, hepatocyte-derived cells seem to show preferential uptake of LNPs containing ionizable lipids with pKa values between 6.2-6.8. The territorial origin of cells also influences their response; cells from metabolically active tissues (liver, kidney) generally show higher transfection rates compared to cells from immune-privileged sites (brain, testes). This specificity may be attributed to differences in apolipoprotein binding patterns, which could be influenced by the ionizable lipid structure and surface charge distribution of the LNPs.

The role of ionizable Lipids in territorial targeting depending on the injection site

The nature of the ionizable lipids profoundly impacts LNP biodistribution in tissue targeting depending on the route of injection¹. Following intraperitoneal injection, LNPs first encounter peritoneal fluid and resident immune cells before systemic absorption. Although still poorly understood, it was observed that ionizable lipids with lower pKa values (6.0-6.5) show enhanced uptake by peritoneal macrophages and mesothelial cells², while those with higher pKa values (6.8-7.2) have greater systemic distribution to liver and spleen⁵. Intramuscular injection favors local muscle cell transfection with lipids containing unsaturated tails⁶, whereas intravenous administration requires lipids that promote ApoE binding for hepatic targeting³. The injection site essentially determines the first biological barriers encountered, and optimal ionizable lipid selection must account for these route-specific challenges to achieve desired tissue targeting.

Results

Ionizable lipid for in vitro mRNA delivery

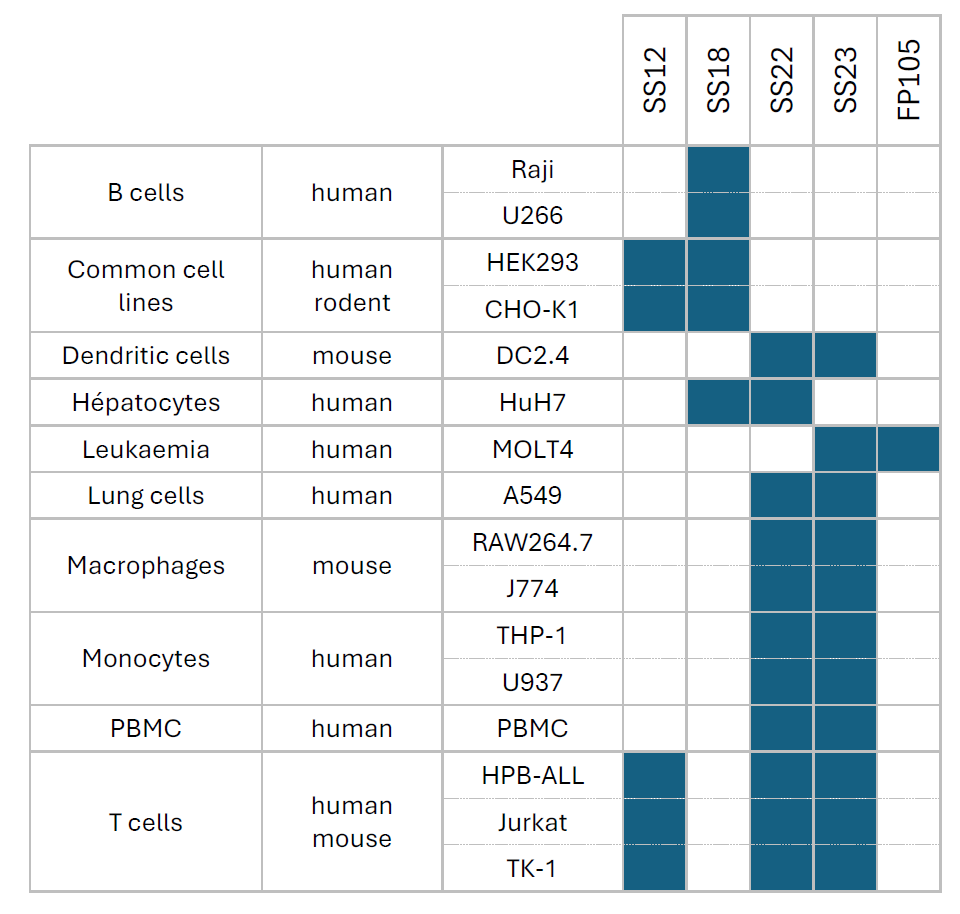

We have demonstrated that depending on their composition or concentration in ionizable lipid or associated components, LNPs present different affinity to efficiently transfect cells from various origins. mRNA-GFP encoding for green fluorescent protein was encapsulated in LNPs formulated with ionizable lipids issued from our proprietary catalog. Various cell types from different origins were then transfected and GFP expression was monitored 24H later by fluorescence microscopy and Flow Cytometry.

The results confirmed that the ionizable lipids have a direct influence on the transfection, depending on the territory from which they originate (Table 1). LNP SS22 or LNP SS23 will be more recommended for dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages and PBMC. Both of them are also good candidate for T cells as well as LNP SS12 whereas B cells will be more prone to be transfected by LNP SS18. Hepatocytes on the other hand would prefer SS18 or SS22, and SS23 or FP105 would be recommended for leukemia cells. Finally, transfection of common cell lines would be more efficient with LNP SS12 or SS18.

| Cell Type | Origin | Standard QC | Ionizable lipid recommended |

| B cells | human |

Raji U266 |

SS18 |

| Common cell lines |

human rodent |

HEK293 CHO-K1 |

SS12 | SS18 |

| Dendritic cells | mouse | DC2.4 | SS22 | SS23 |

| Hépatocytes | human | HuH7 | SS18 | SS22 |

| Leukaemia | human | MOLT4 | FP105 | SS23 |

| Lung cells | human | A549 | SS22 | FP105 |

| Macrophages | mouse |

RAW264.7 J774 |

SS22 | SS23 |

| Monocytes | human |

THP-1 U937 |

SS22 | SS23 |

| PBMC | human | PBMC | SS22 | SS23 |

| T cells |

human mouse |

HPB-ALL Jurkat TK-1 |

SS12 | SS 22 | SS23 |

Table 1: Recommended ionizable lipids to use as complexing lipid for LNP formulation depending on cell type and origin. Various types of cell lines from different origins were transfected with mRNA-LUC or -GFP encapsulated in LNP formulated with OZB catalogue of ionizable lipids. The best candidate(s) for each cell type were chosen according to the efficiency of transfection.

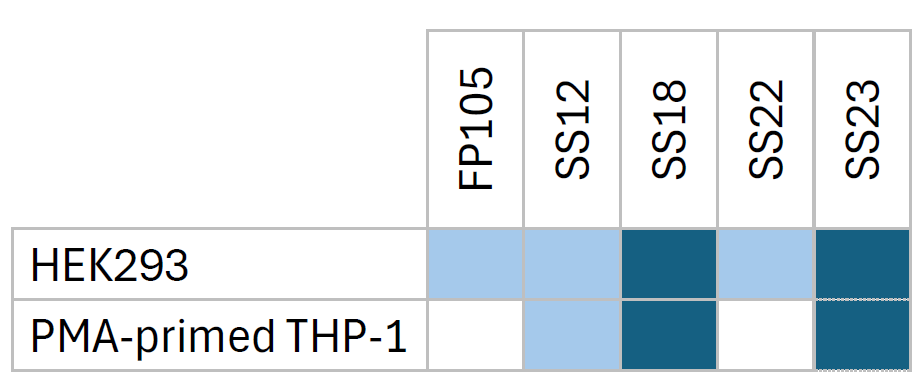

We can then spot for each cell type which LNP works the best to draw a pattern allowing to choose more easily which lipid to recommend for which application (Table 2):

Table 2: Choice of ionizable lipid for mRNA-LNP formulation depending on the cell type and territory

Ionizable lipid for in vivo mRNA delivery

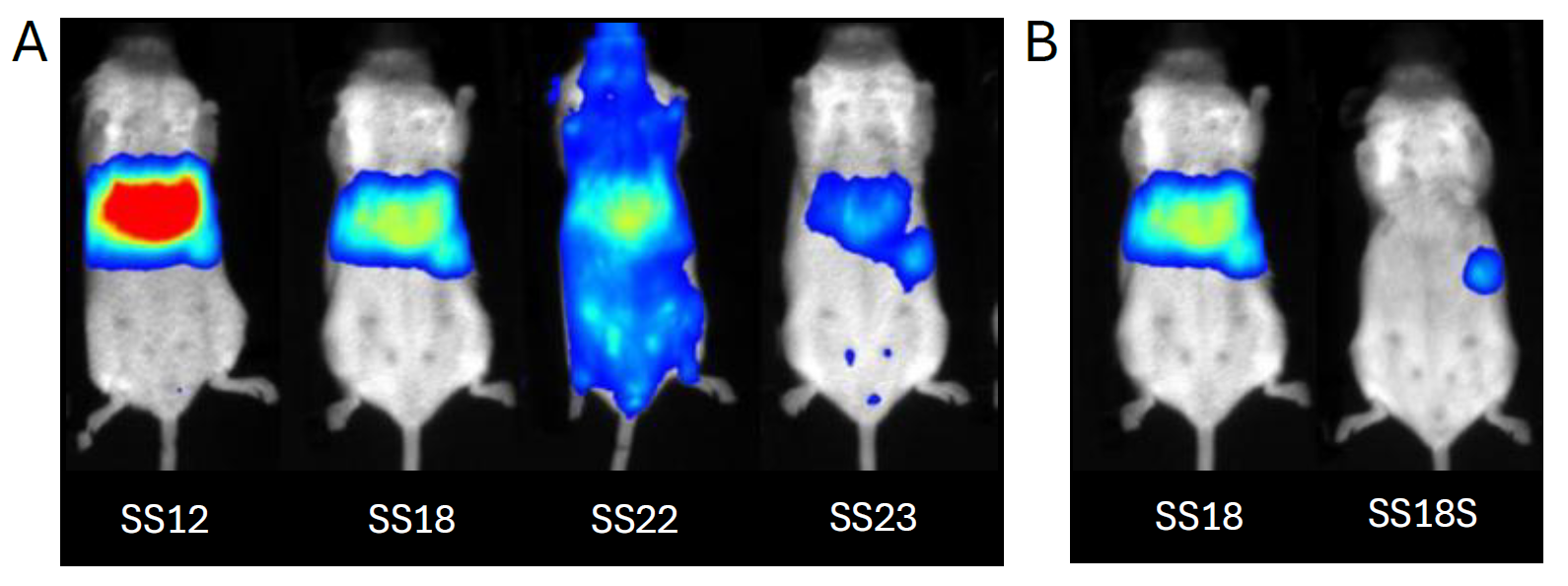

In this section we have shown that the formulating mRNA-LUC lipid nanoparticles while varying ionizable lipid affects transfection localization within the body. mRNA encoding for Luciferase (#MRNA16-100) was encapsulated in LNPs formulated using ionizable lipids from our proprietary catalog. The LNPs were then injected intravenously into mice and luciferase expression was monitored 24H after by intraperitoneal injection of D-Luciferin.

The localization and intensity of luminescence expression varied according to the composition of LNPs, both in terms of the type and amount of ionizable lipids and associated components that would affect their size and charge. Some would be directed to a single territory, some would be more or less efficient to transfect cells, and others would have full body distribution.

Among the best candidates, we set up a group of 5 different ionizable lipids (SS12, SS18, SS22, SS23 & FP105) that presented the highest transfection efficiency following mouse intravenous injection.

Figure 2 (A) shows how different zones can be addressed by LNP made with different lipids following intravenous administration. When SS22 is used, transfection is widespread across the body with some peak of luminescence expression in the liver and the hindlimbs that seem to indicate a full body distribution. LNP formulated with SS12 on the contrary go preferentially to the liver and induce a high luciferase expression. LNP SS18 & SS23 present the same behavior with an additional uptake in the spleen.

In the same experiment, we have modified the constituents (nature and concentration) composing LNP SS18. Figure 2 (B) demonstrates that we can reduce liver uptake and re-orientate the delivery with an expression that is now predominantly localized in the spleen.

Figure 2: Spatial distribution and intensity of transfection in mouse following intravenous administration of mRNA-LUC encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles (LNP) using ionizable lipids SS12, SS18, SS18S, SS22, and SS23. (A) LNP uptake depends on the ionizable lipid: liver (SS12), spleen (SS18 & SS23) or full body can be reached (SS22). (B) Change in the composition of the LNP using ionizable lipid SS18 or SS18S shifts organ targeting from the liver to the spleen.

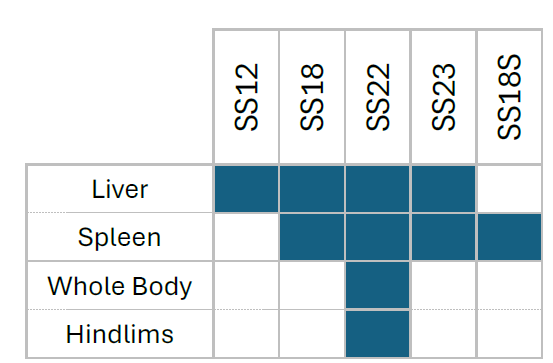

We can thus fill in a table that shows what ionizable lipid can be used to formulate LNP in order to target a specific territory following intravenous injection in mouse (Table 3). This table can be used to choose wisely which lipid or modification for in vivo experiment.

Table 3: Choice of ionizable lipid for LNP formulation depending on the desired territory to transfect following intravenous injection.

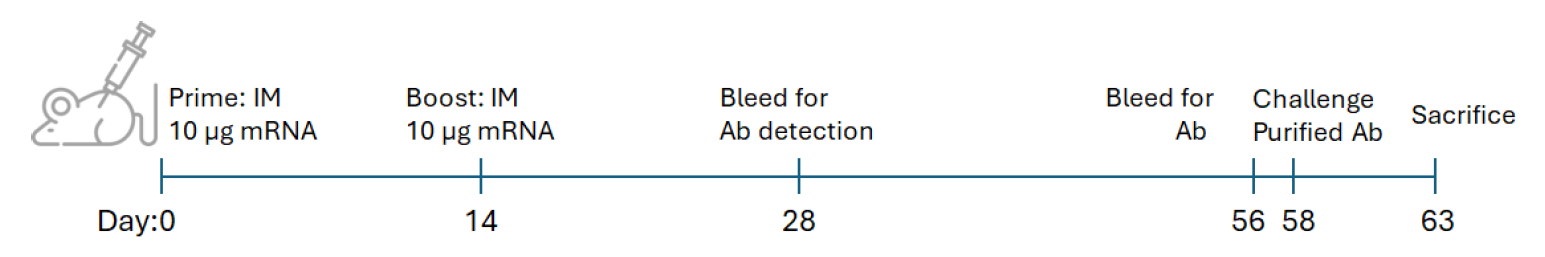

Ionizable lipid for Immunization

We have evaluated the immunogenicity of different lipid nanoparticles formulation for delivering mRNA encoding antigen in mice. Seven groups of mice (n=5 each) were tested, including untreated controls and treatment groups comparing LNP formulations (based on FP105 and FP115 ionizable lipids, and 3 other LNPs -a, -b & c) with and without mRNA. Using a prime-boost immunization strategy, mice received intramuscular injections of 10 μg mRNA on day 0 and 14. Immune responses were monitored through blood collection on days 28 and 56 for antibody detection, followed by a challenge with purified antigen on day 58. The study concluded on day 63 with tissue collection including thighs for B cell isolation, popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes for immune cell analysis, and sera for comprehensive antibody measurements to assess the relative efficacy of each LNP formulation in generating protective immunity depending on the choice of lipid (figure 3).

Figure 3: Experimental design for LNP-mRNA immunization in mouse and challenge study. This schematic illustrates the immunization after intramuscular injection of LNP-mRNA and challenge protocol for mice (n=5 per group).

In a parallel experiment we have investigated the immunogenicity of various lipid nanoparticle formulations for delivering mRNA encoding an antigen in mice by subcutaneous injection. Mice received two doses of vaccination using 5 μg mRNA formulated into ionizable lipids-LNP and blood samples were withdrawn each week for 8 weeks.

The results demonstrated that ionizable lipids FP105 and FP115 were 2 interesting candidates for mouse vaccination (Table 4).

Table 4: Choice of ionizable lipid for mRNA-LNP formulation for immunization in mice depending on the site of injection.

Ionizable lipid for gene silencing

LNP-siRNA hold a great potential not only in Research but also show great promises in Therapeutics since many LNP-siRNA based drugs are approved by the FDA such as for example Onpattro for treating Transthyretin Amyloidosis. This is due to the characteristics of these vectors to efficiently deliver the siRNA in various sites depending on LNP generation. Moreover, these vectors are very stable, conferring a prolonged effect (up to 6 months). Chemically speaking, the versatility and the adaptiveness of our LNP mainly comes from their composition with the choice of the ionizable lipid or their decoration with targeting ligands. The creation of any kind of LNP, decorated or not, with our own ionizable lipid or existing ones can be addressed by our LNP platform.

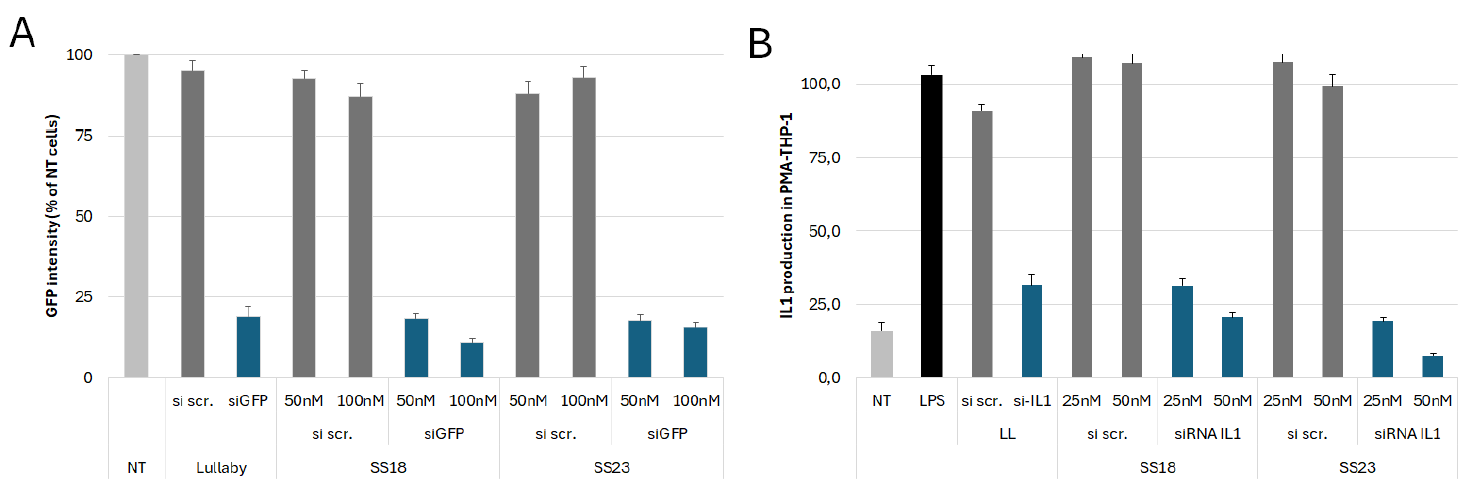

Considering siRNA, we have designed new LNP based on our catalog of ionizable lipid to specifically deliver siRNA aiming at silencing gene expression both in vitro and in vivo. First, a screening was performed using HEK293 cell line expressing GFP to find the best ionizable lipid and LNP composition able to efficiently silence GFP expression. LNP-SS18 and SS23 showed the most important gene silencing 72H after transfection (Figure 4.A). These LNPs were then evaluated in more functional and physiologically relevant model of IL-1 production. PMA primed THP-1 were stimulated during 4 hours with LPS and then transfected with siRNA-IL1 or scramble encapsulated in LNP. 72H after, the production of IL-1 was measured by ELISA and we confirmed that LNP-SS18 and SS23 were ideal to deliver siRNA in vitro (Figure 4.B).

Figure 4: Evaluation of gene silencing efficiency in vitro following siRNA-LNP SS299 and SS23 transfection. (A) HEK293-GFP were transfected with siRNA scrambled (si scr.) or siRNA targeting GFP (siGFP) encapsulated in LNP and GFP intensity was measured 72H after by flow cytometry. (B) Dosage of IL-1 by ELISA in PMA primed THP-1 stimulated with LPS and transfected with si scr. or siRNA targeting IL-1 (siRNA IL1) encapsulated in LNP.

Other ionizable lipids were evaluated in parallel and allowed to silence also gene expression in the two experimental models (data not shown). These results allow us to draw up a table of lipids that can be used to formulate siRNA-LNP aiming at silencing gene expression.

Table 5: Choice of ionizable lipid for siRNA-LNP formulation for gene silencing in HEK293 and macrophages.

siRNA LNP are being tested in vivo in rabbit models of osteoarthritis during the SINPAIN European grant (HORIZON-HLTH-2021-TOOL-06-02). The SINPAIN program aims to develop a pipeline of siRNA-based therapy built on the combination of nanocarriers that will be designed to reach a successful management of inflammation and innervation therapy for the treatment of early (grade 0-1) and later stages (grade 3-4) of knee osteoarthritis. The capacity of the ionizable lipids used to formulate LNP that encapsulates, protects and delivers siRNAs should demonstrate the reduced inflammation and pain, as well as the cartilage regeneration.

Conclusions & future directions

This study demonstrates that ionizable lipid composition is the primary determinant of LNP performance in both in vitro and in vivo settings. With the capacity to modulate composition, charge and size, our LNP platform is able to produce LNPS that can address various zones in the body. As observed, modification of the ionizable lipid can shift organ targeting with LNP that evades liver to target more preferentially the spleen. The data supports a rational design approach where lipid selection is based on target cell type and intended route of administration.

Further optimization of ionizable lipids for cell-type specific delivery remains a priority. Development of lipids with tunable pKa values and biodegradable structures will enhance both efficacy and safety profiles of mRNA therapeutics.

Author: Cédric Sapet, PhD.

References

¹ Cheng, Q., Wei, T., Farbiak, L., Johnson, L. T., Dilliard, S. A., & Siegwart, D. J. (2020). Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR–Cas gene editing. Nature Nanotechnology, 15(4), 313-320.

² Miao, L., Li, L., Huang, Y., Delcassian, D., Chahal, J., Han, J., ... & Anderson, D. G. (2020). Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nature Biotechnology, 38(10), 1310-1322.

³ Patel, S., Ashwanikumar, N., Robinson, E., Xia, Y., Mihai, C., Griffith, J. P., ... & Sahay, G. (2020). Naturallyoccurring cholesterol analogues in lipid nanoparticles induce polymorphic shape and enhance intracellular delivery of mRNA. Nature Communications, 11(1), 983.

⁴ Dilliard, S. A., Cheng, Q., & Siegwart, D. J. (2021). On the mechanism of tissue-specific mRNA delivery by selective organ targeting nanoparticles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(52), e2109256118.

⁵ Paunovska, K., Da Silva Sanchez, A. J., Sago, C. D., Gan, Z., Lokugamage, M. P., Islam, F. Z., ... & Dahlman, J. E. (2022). Nanoparticles containing oxidized cholesterol deliver mRNA to the liver microenvironment at clinically relevant doses. Advanced Materials, 34(9), 2103397.

⁶ Hajj, K. A., Ball, R. L., Deluty, S. B., Singh, S. R., Strelkova, D., Knapp, C. M., ... & Whitehead, K. A. (2021). Branched-tail lipid nanoparticles potently deliver mRNA in vivo due to enhanced ionization at endosomal pH. Small, 17(6), 2005671.